Addressing what liquidity in private market allocations means and why it isn’t a reason for zero allocation

Defined contribution (DC) plans exist to maximize retirement income, not provide unlimited daily access to savings. In our first paper, Zero Is Not the Answer, we outlined why professionally managed solutions that incorporate private markets can help achieve long‑term retirement income outcomes. Liquidity, or perceived illiquidity, often surfaces as a common objection, driven by the misconception that participants need 100% daily liquidity. This paper clarifies how DC plan liquidity actually works, why thoughtfully sized illiquidity can support better outcomes, and how fiduciaries manage liquidity, even in stress scenarios.

Bottom line:

Excluding private assets entirely is not the solution—DC plans can balance liquidity and long-term growth without defaulting to zero allocation.

Defining liquidity in DC plans

To understand why daily liquidity isn’t necessary, let’s start with what liquidity really means in this context. In DC plans, there are two types of liquidity: participant‑level (often referred to as benefit‑responsive) and plan‑level.

Participant‑level liquidity covers scheduled, policy‑driven portfolio maintenance and distributions for individuals executed by the investment manager and recordkeeper on a defined cadence. Plan‑level liquidity is managed centrally for the pooled vehicle. Participant transactions are fulfilled via netting of inflows/ outflows and the plan’s liquid sleeves or cash buffers, not by selling each individual’s underlying positions. Understanding these two levels prevents a common misunderstanding—that every participant action must trigger security‑level sales.

DC plans are built to convert savings into retirement income, covering everyday needs like groceries, housing, utilities, and healthcare in the years ahead. Before retirement age, access is intentionally limited by tax policy, early‑withdrawal penalties, and loan restrictions to support that long‑term objective. Within that design, liquidity is structured to meet scheduled needs (e.g., rebalancing, staged allocation changes, and required distributions), and expecting 100% daily liquidity across a participant’s balance doesn’t reflect how DC plans are intended to serve participants over the long term.

Participant-level liquidity in practice

Participant level liquidity in professionally managed accounts supports fiduciary objectives: disciplined rebalancing and staged allocation changes that keep participants on track for retirement income within their risk tolerance. Fiduciaries set targets and tolerance bands and delegate implementation to the investment manager and recordkeeper on a defined cadence (e.g., quarterly or annually). For illustration, many investment policy statement (IPS) frameworks use tolerance bands around strategic targets, e.g., a 60% equity target monitored within ±5 percentage points.1 Rebalancing is triggered at the scheduled cadence or when drift breaches the policy guardrails, optimizing execution, managing volatility, and controlling costs to improve net, risk adjusted outcomes.

For example, Participant 1 targets 60% Equity / 25% Fixed Income / 15% Private Markets (60/25/15) in their 401(k). On Monday, Participant 1 is aligned with the target. Due to market conditions, equity drifts to 66%, breaching the established 55–65% band and triggering a rebalance. No rule or law requires the plan to reset by Friday’s close to be back at 60/25/15 by Monday’s open; changes are only executed on the agreed schedule. Likewise, if Participant 1 determines 60/25/15 is too conservative and a 70/15/15 mix better aligns with their goals and risk tolerance, that strategic shift is typically staged over time to optimize execution, manage volatility, and control costs.

Plan-level liquidity in practice

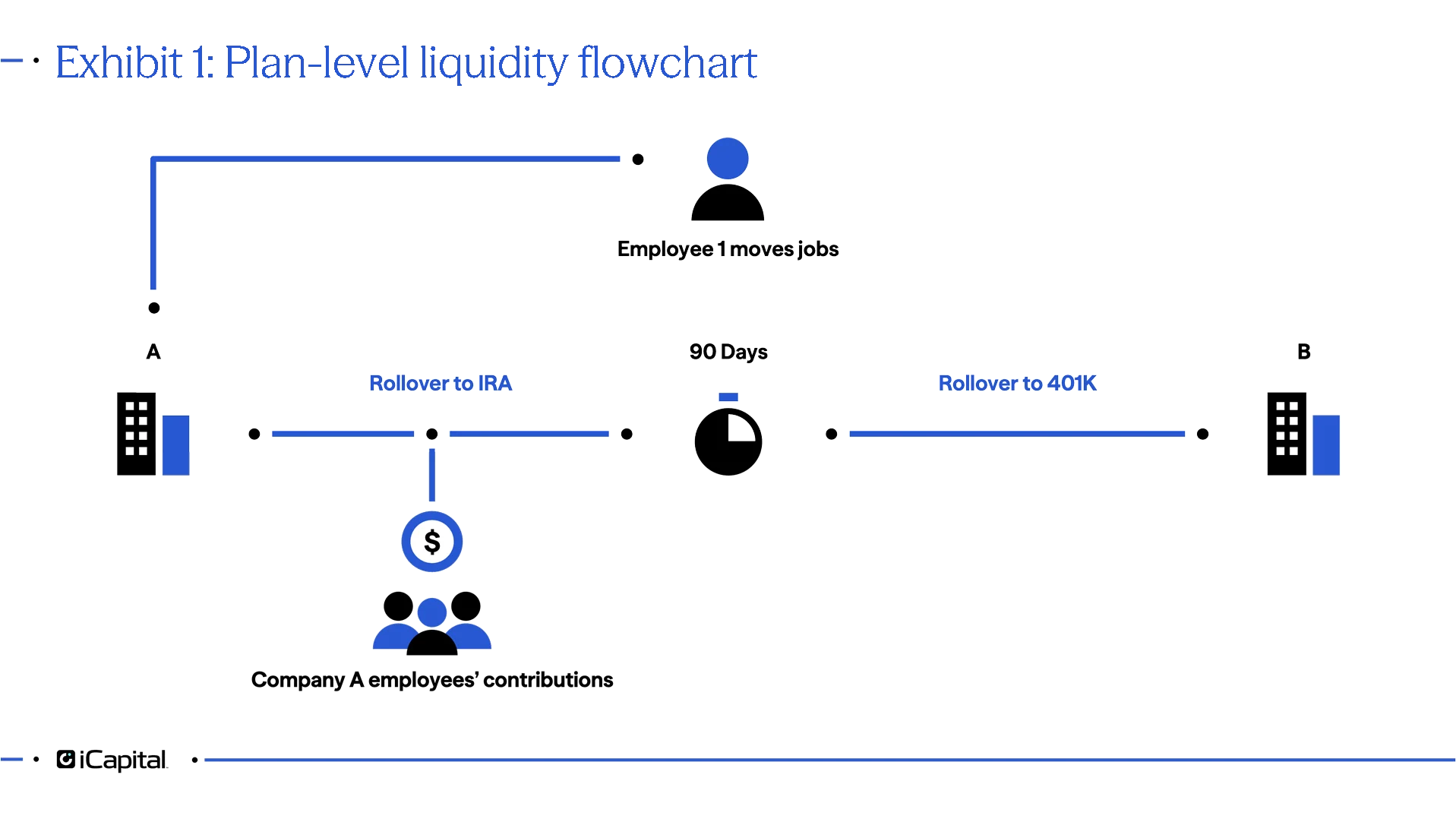

Plan‑level liquidity is managed centrally for the pooled vehicle. Participant transactions are fulfilled via netting of inflows/ outflows and the plan’s liquid sleeves or cash buffers, not by selling each individual’s underlying positions. When a participant separates and initiates a rollover, distributions are typically met at the plan level through ongoing contributions and liquid sleeves or cash buffers without selling that individual’s underlying positions, because the plan holds the position, not the individual (see Exhibit 1).

Source: iCapital illustration: Plan-level liquidity fulfills participant rollovers using contributions and netting—not by selling individual positions. For illustrative purposes only.

Exploring the worst-case scenario

A rare but instructive case is a mass layoff in which many participants invested in a target date fund (TDF) with a modest illiquid sleeve all request immediate rollovers into IRAs. In this scenario, advance notice may be limited, and blackout periods may be impractical. Typically, it is unlikely that all laid-off participants are going to request an IRA rollover on day one of their separation.

But what happens if they do? Once the layoff is announced, the plan immediately notifies their TDF manager, who must quickly assess a range of factors to manage liquidity responsibly, including: plan demographics; average participant balances; asset allocations; the projected outflows in relation to the inflows from employees who will remain with the company; and participant withdrawal patterns. Following this analysis, if needed, temporary gating consistent with plan provisions may be used—as a last resort—to prevent harm to remaining participants. Even in this worst‑case scenario, the event is manageable by the fiduciary whose role is to reduce risk to the plan and participants while honoring benefit‑responsive obligations.

The lesson is clear: plan‑level liquidity management, not 100% daily liquidity, is the appropriate tool, so edge‑case stress events do not justify a zero allocation to private markets.

Structured liquidity solutions

Beyond the plan’s cash buffers and liquid sleeves, fiduciaries can use evergreen, interval, and tender-offer vehicles to provide scheduled interim access with regular NAVs and manager oversight. These features align with participant-level policy cadence and central plan-level fulfillment.

Evergreen vehicles deploy capital continuously and offer periodic redemptions (rather than daily liquidity) helping to reduce J-curve and capital call frictions associated with traditional drawdown structures. Meanwhile, DC obligations such as rebalances, staged allocation changes, and required minimum distributions (RMDs) continue to be met centrally from the plan’s liquid architecture.

Interval and tender-offer sleeves introduce predictable windows for interim liquidity, typically monthly or quarterly with stated capacity and notice, allowing sponsors and recordkeepers to plan and budget effectively. The ecosystem has expanded meaningfully with more institutional-style pricing, structure, transparency, and education, making these vehicles practical building blocks inside professionally managed DC solutions. Coordinated with netting and ongoing contributions, these mechanisms preserve the portfolio’s long-term retirement objective while avoiding security-level sales.2

Illiquidity as a constructive feature

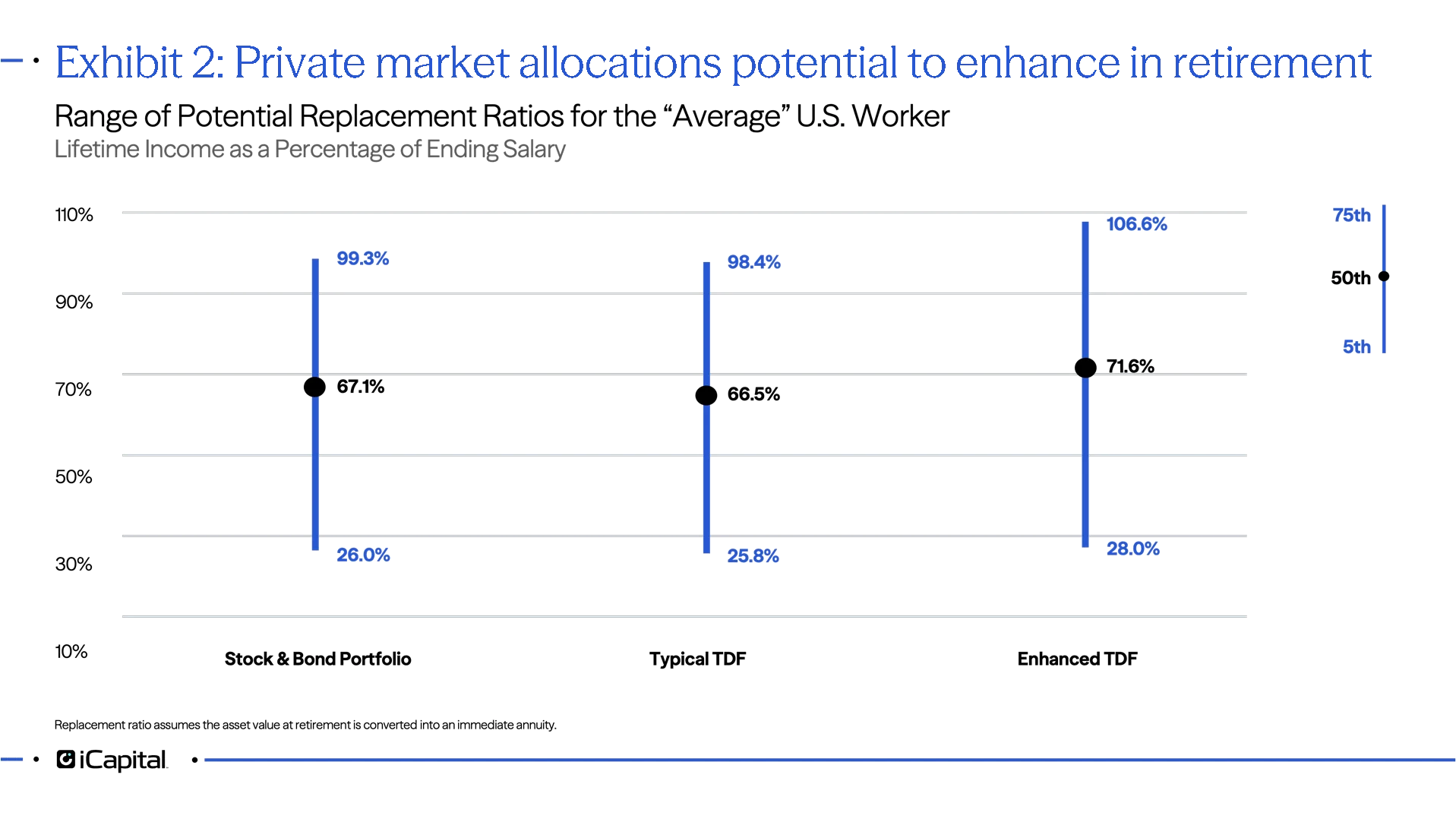

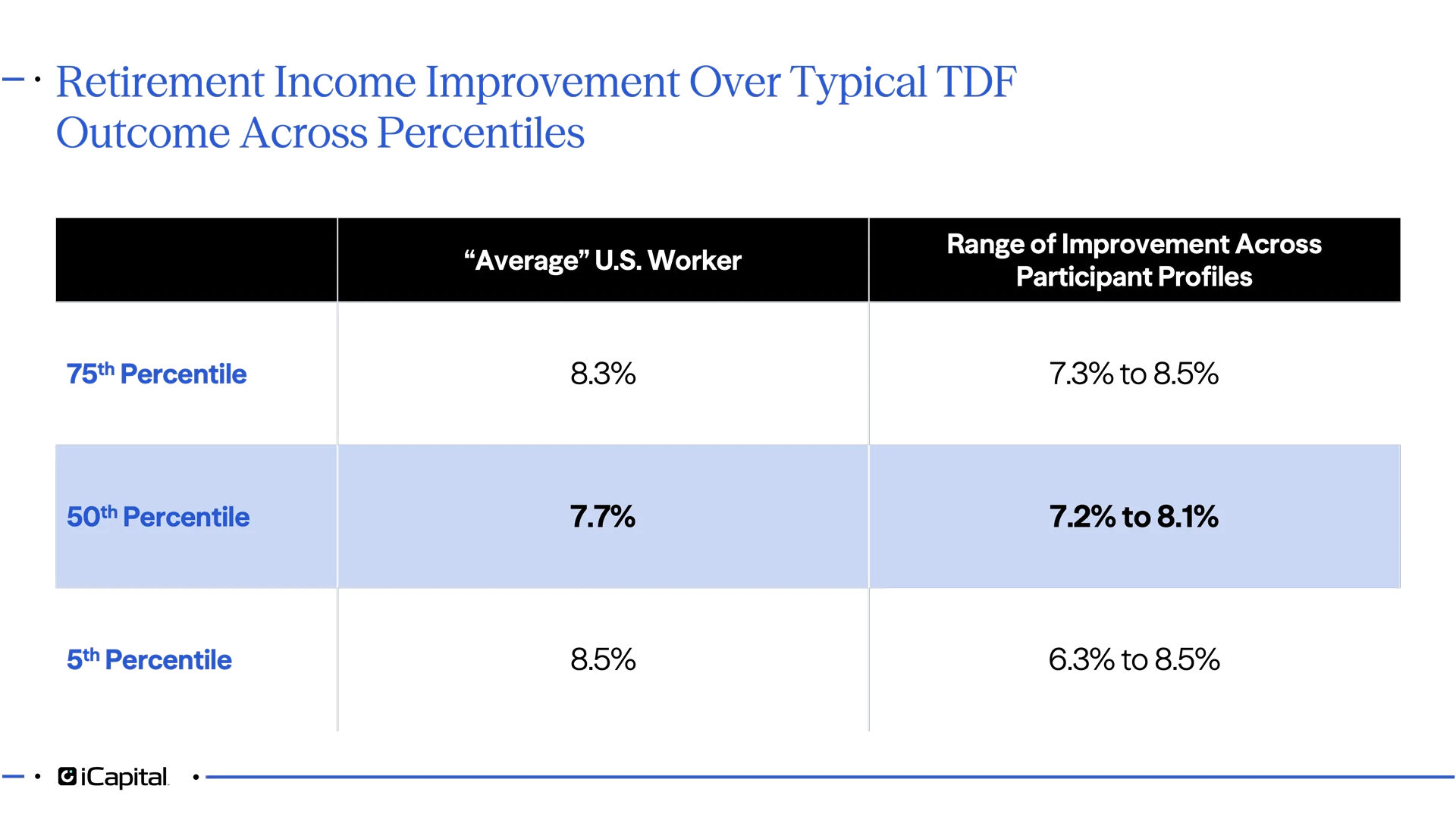

With mechanics clarified, let’s turn to why illiquidity can potentially improve outcomes. Research by Angela Antonelli of Georgetown University’s Center for Retirement Initiatives supports this view, showing that private market allocations can enhance income replacement in retirement (see Exhibit 2).3 By including real assets and private credit in glidepaths, plans can generate more stable and potentially higher income streams.

Source: Angela Antonelli. “Making the Case: The Effect of Private Market Assets on Retirement Income in Cases of Disrupted Savings,” Georgetown University Center for Retirement Initiatives, August 2025. For illustrative purposes only.

The next question is why a measured illiquid sleeve belongs at all: because it can help participants stay invested and pursue better net, risk-adjusted retirement income over time. Foundational behavioral economics research by John Beshears et. al.4 and recent modeling by Benartzi Labs5 in collaboration with the Defined Contribution Alternatives Association (DCALTA) both suggest that participants often prefer illiquidity, as limited access to their portfolio funds helps to curb impulsive financial decisions and withdrawals that undermine their long-term goals.

“Illiquidity, in this context, is a feature, not a flaw, of retirement planning.”

Benefit-responsive liquidity and illiquid assets

Now that we’ve defined liquidity in the context of retirement planning, how does benefit-responsive liquidity work with illiquid assets? A common misconception is to treat DC plans as a collection of mini‑brokerage accounts—as if every participant action (rollover, rebalance, or allocation change) must trigger sales inside that individual’s account, including any illiquid sleeves. This is not how DC plans operate. As defined earlier, participant actions are fulfilled at the plan level via netting and liquid sleeves. The result: benefit‑responsive needs are met while modest illiquid sleeves (e.g., private real estate, infrastructure, private credit) remain aligned to long‑term objectives. The same principle applies during the drawdown phase of a retirement glidepath. A professionally managed portfolio would rebalance to meet participant objectives.

For example, the 60/25/15 allocation noted earlier could be rebalanced to 44/44/12 as the participant approaches retirement, and further adjusted to something like 35/55/106 ten years into post-retirement. Reducing private market exposure via rebalancing increases portfolio liquidity as the participant shifts from accumulation to drawdown—similar to reducing equity exposure and increasing fixed income allocations.

The role of liquidity in the drawdown phase introduces another common misconception: that participants reaching RMD age will be unable to receive their RMD because private market lockup periods prevent asset sales without penalties or losses. In reality, average RMDs are typically modest (see sidebar: Calculating RMDs with Illiquid Assets); withdrawals may be satisfied from liquid sleeves within the portfolio, with minimal impact on target allocations. Additionally, many private market assets, such as real estate, infrastructure, and credit, generate income that can help meet RMD obligations without selling underlying positions. This shift toward income-generating private assets is typically part of glidepath-driven rebalancing.

As noted earlier, structured liquidity vehicles such as evergreen, interval, and tender-offer funds complement this design by providing predictable access points without compromising the portfolio’s long-term objectives. These mechanisms reinforce the system’s ability to keep participants invested while meeting benefit-responsive needs.

Calculating RMDs with illiquid assets7

There are other ways to manage withdrawals, but here are two examples of the how illiquid assets would factor into an RMD:

Using median 401(k) data ($95,425), a 73-year-old participant would face an RMD of approximately $3,600 annually, or $300 monthly. With diversified glidepaths including 5% allocations to real assets and private credit, the monthly liquidity need from these sleeves is minimal—around $15 each.

Using the average 401(k) data ($299,442), a 73-year-old participant would face a RMD of approximately $11,300 annually, or $940 monthly. With diversified glidepaths including 5% allocations to real assets and private credit, the monthly liquidity need from these sleeves is also minimal—around $50 each.

Managing plan level illiquidity

Liquidity restrictions are not new to DC plans. They are common and well-managed. Stable value funds, found in over 80% of large DC plans8 and representing over US$ 850 billion9 of the assets in the 401(k) system,10 include put provisions requiring advance notice (often 3–12 months) before large withdrawals. These provisions ensure fund managers can meet redemptions without harming remaining participants. Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) are another common feature of 401(k) plans that require funding and liquidity planning by the plan sponsor. Some liquidation events can be planned, such as vesting cliffs or retirements, and some cannot, such as terminations or resignations. Either way, DC plans manage these events regularly and have for decades.

In cases of plan mergers, such as during corporate acquisitions, liquidity issues can also be planned and managed. These are not surprise events. For example, large Company A, with 10,000 DC participants and US$1 billion in plan assets, acquires smaller Company B, with 1,000 DC participants and US$100 million in plan assets. This acquisition may trigger a liquidation of Company B’s plan assets, but there is no provision in the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974 that requires the plans to merge overnight. The plan merger can be scheduled and managed based on the assets held in both plans, working in conjunction with recordkeepers, advisors and consultants, and asset managers to unwind positions over a period that protects each plan’s participants and assets.

Fiduciaries play the central role in navigating these transitions, adjusting asset mixes, and ensuring participant protections. This role is the same whether the plan is 100% liquid or 80% liquid. What may change is the period required to merge the plans—and in rare stress conditions, the same plan level tools apply. (See “Calculating RMDs with Illiquid Assets”).

Conclusion

As regulatory guidance continues to evolve, the conversation around liquidity in DC plans will likely become more nuanced. What is already abundantly clear is that excluding private assets entirely due to liquidity concerns is not the answer because DC plans already manage liquidity as part of their day-to-day operations.

A measured illiquid sleeve within properly designed, professionally managed solutions, e.g., qualified default investment alternatives (QDIAs), TDFs, and managed accounts, aligns with the long-term nature of retirement investing. They support behavioral discipline, can enhance income potential, and reflect U.S. tax policy’s intent to encourage saving for retirement. Moreover, they balance liquidity across accumulation and drawdown while keeping participants invested for outcomes consistent with their risk tolerance.

“Put simply, managed liquidity of alternative investments does not justify zero allocation.”

The next paper in this series turns to the fiduciary’s toolkit— policy, sizing, vehicles, and manager oversight—to translate liquidity into better, risk‑aligned retirement outcomes.

ENDNOTES

- See: William W. Jennings, PhD, CFA, and Eugene L. Podkaminer, CFA , “Overview of Asset Allocation,” CFA Institute, CFA Program Curriculum, 2023.

- See: “The Road to Mass Adoption – Evergreen Funds: Amplifying Client Adoption,” iCapital, June 17, 2025.

- Source: Angela M. Antonelli, “Making the Case: The Effect of Private Market Assets on Retirement Income in Cases of Disrupted Savings.” Georgetown University Center for Retirement Initiatives in conjunction with WTW. 2025. Note: This study analyzed a range of DC plan participants (e.g., Lower-Income Workers; Family Caretakers; Job Hoppers; Unexpected Early Retirement; and an “Average” participant) that roughly model a typical plan.

- See: John Beshears, James J. Choi, Christopher Harris, David Laibson, Brigitte C. Madrian, and Jung Sakong. “Self Control and Commitment: Can Decreasing the Liquidity of a Savings Account Increase Deposits?,” NBER Working Paper 21474 (2015), https://doi.org/10.3386/w21474; John Beshears, James J. Choi, Joshua Hurwitz, David Laibson, and Brigitte C. Madrian, “Liquidity in Retirement Savings Systems: An International Comparison,” NBER Working Paper 21168 (2015), https://doi.org/10.3386/w21168; John Beshears, James J. Choi, Christopher Clayton, Christopher Harris, David Laibson, Brigitte C. Madrian, “Optimal illiquidity,” Journal of Financial Economics, Volume 165, (2025), https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jfineco.2025.103996.

- See: Shlomo Benartzi. “A Pilot to Document the Underlying Demand for Alts,” Benartzi Labs + DCALTA. As of November 30, 2025.

- For examples of how this can be managed through a TDF, see: Angela M. Antonelli, “Making the Case: The Effect of Private Market Assets on Retirement Income in Cases of Disrupted Savings.” Georgetown University Center for Retirement Initiatives in conjunction with WTW. 2025.

- Note: All figures rounded. Methodology: Total Asset Balance / 26.5 / 12 months X .5% allocation. Average and mean portfolio data source, using the 65-year-old plus age category: Vanguard. How America Saves 2025. Data as of December 31, 2024.

- Sources: Jamie McAllister et al. 2024 DC Trends Survey. Callan Institute. April 24, 2024; Stable Value Investment Association. Stable Value at a Glance. Data as of September 18, 2025.

- Source: Jamie McAllister et al. 2024 DC Trends Survey. Callan Institute. April 24, 2024

- Source: Stable Value Investment Association. Stable Value at a Glance. Data as of September 18, 2025.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

The material herein has been provided to you for informational purposes only by Institutional Capital Network, Inc. (“iCapital Network”) or one of its affiliates (iCapital Network together with its affiliates, “iCapital”). This material is the property of iCapital and may not be shared without the written permission of iCapital. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission of iCapital.

This material is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended as, and may not be relied on in any manner as, legal, tax or investment advice, a recommendation, or as an offer or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument, or otherwise to participate in any particular trading strategy.

This material does not intend to address the financial objectives, situation, or specific needs of any individual investor. You should consult your personal accounting, tax and legal advisors to understand the implications of any investment specific to your personal financial situation.

ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS ARE CONSIDERED COMPLEX PRODUCTS AND MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR ALL INVESTORS. Prospective investors should be aware that an investment in an alternative investment is speculative and involves a high degree of risk. Alternative Investments often engage in leveraging and other speculative investment practices that may increase the risk of investment loss; can be highly illiquid; may not be required to provide periodic pricing or valuation information to investors; may involve complex tax structures and delays in distributing important tax information; are not subject to the same regulatory requirements as mutual funds; and often charge high fees. There is no guarantee that an alternative investment will implement its investment strategy and/or achieve its objectives, generate profits, or avoid loss. An investment should only be considered by sophisticated investors who can afford to lose all or a substantial amount of their investment.

iCapital Markets LLC operates a platform that makes available financial products to financial professionals. In operating this platform, iCapital Markets LLC generally earns revenue based on the volume of transactions that take place in these products and would benefit by an increase in sales for these products.

The information contained herein is an opinion only, as of the date indicated, and should not be relied upon as the only important information available. Any prediction, projection or forecast on the economy, stock market, bond market or the economic trends of the markets is not necessarily indicative of the future or likely performance.

The information contained herein is subject to change, incomplete, and may include information and/or data obtained from third party sources that iCapital believes, but does not guarantee, to be accurate. iCapital considers this third-party data reliable, but does not represent that it is accurate, complete and/or up to date, and it should not be relied on as such. iCapital makes no representation as to the accuracy or completeness of this material and accepts no liability for losses arising from the use of the material presented. No representation or warranty is made by iCapital as to the reasonableness or completeness of such forward-looking statements or to any other financial information contained herein.

Securities products and services are offered by iCapital Markets LLC, an SEC-registered broker-dealer, member FINRA and SIPC, and an affiliate of iCapital, Inc. and Institutional Capital Network, Inc. These registrations and memberships in no way imply that the SEC, FINRA, or SIPC have endorsed any of the entities, products, or services discussed herein. Annuities and insurance services are provided by iCapital Annuities and Insurance Services LLC, an affiliate of iCapital, Inc. “iCapital” and “iCapital Network” are registered trademarks of Institutional Capital Network, Inc. Additional information is available upon request.

© 2025 Institutional Capital Network, Inc. All Rights Reserved